Although arguably the best known of the group, Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm were hardly the only 19th century European scholars to embark on the study of folklore and publish collections of fairy tales. Indeed, by then, the idea of fairy tale collections stretched back centuries—with authors either proudly presenting fairy tales inspired by oral sources or earlier written versions as their own creations, or, more modestly, claiming that the tales they carefully crafted were taken from stories they had heard as children. Those collections continued to be penned throughout the 19th century, augmented by academic studies that presented fairy tales as an important part of culture, often as part of creating nation states and national identity.

Among these scholars were Norwegian scholars Peter Christen Asbjørnsen and Jørgen Engebretsen Moe, better known to history as simply Asbjørnsen and Moe, who preserved for us the delightful tale of the “The Three Billy Goats Gruff.”

Peter Christen Asbjørnsen (1812-1885), the son of a glazier, began collecting fairy tales when he was twenty, in between studying zoology at the University of Oslo. He eventually working as a marine biologist and traveling to nearly every single corner of Norway—or at least every fjord, and later became an early, passionate environmentalist, arguing for the preservation of Norway’s forests. He never married, apparently devoting his passions to wildlife and fairy tales.

His friend Jørgen Engebretsen Moe (1813-1882), the son of a wealthy farmer and politician, began collecting fairy tales at the even earlier age of twelve. He also studied theology and literature, earning a position as a professor of theology before entering the church in 1853. Here, he enjoyed a distinguished career, rising from chaplain to parish priest and eventually to bishop, while also penning poems and original short stories for children. That interest in poetry and short stories may have helped shape the final versions of the Asbjørnsen and Moe collections.

The two formed an instant friendship when they first met in 1826, but apparently did not discuss their shared love of fairy tales and folklore until 1834. At that point, they agreed to combine forces and tales. Their first collection, Norske Folkeeventyr (Norwegian Folk Tales) appeared in 1842, swiftly followed by a second volume in 1844. Asbjørnsen released his own collection of fairy tales, Huldre-Eventyr of Folkesagn. Despite a stated concern that some of the tales would “shock English feeling,” Sir George Webbe Dasent translated and published a selection in Popular Tales from the Norse in 1859. That selection included “The Three Billy Goats Gruff.” Both the tale and the collection proved instantly popular.

As the story starts, three billy goats—boy/bambino goats, as a teacher once helpfully explained—have decided to get fat by heading up a hill to eat. I approve of this plan, as would, presumably, most farmers hearing the tale. Unfortunately, the goats face just one tiny—ok, major—roadblock: to reach the amazing, weight increasing food on that hill, they have to cross a bridge with a troll. I suspect that everyone reading this who has ever had to make reservations at a popular restaurant is nodding in sad sympathy. I mean, on the one hand, food, and on the other hand, making reservations—that is, dealing with a troll.

Still, the littlest Billy Goat knows what’s ahead—food—and promptly heads over the bridge, assuring the troll that better, fattier Billy Goats will be coming along at any minute now. The troll actually buys this, and agrees to wait for the next Billy Goat. Who repeats the same thing, convincing the troll to wait for the third goat.

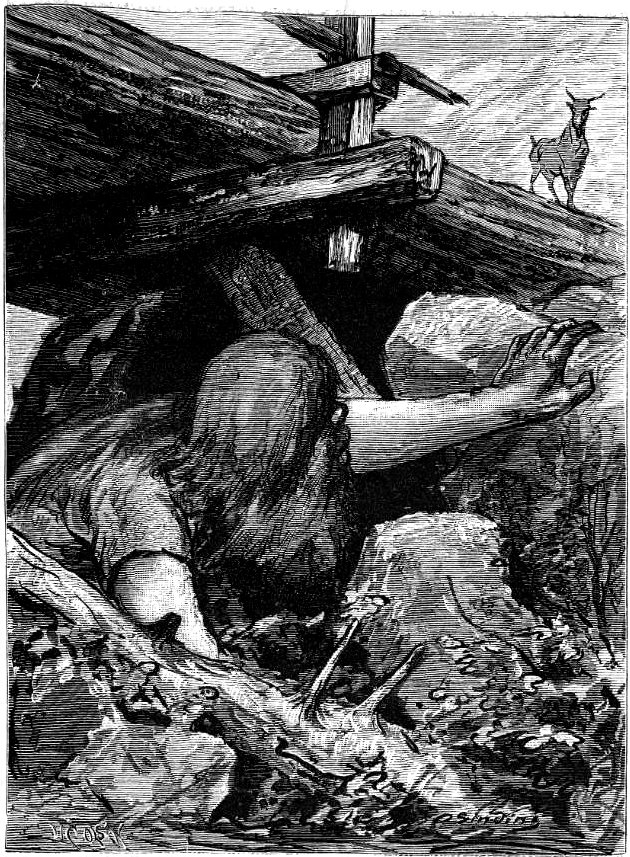

The third Billy Goat, the largest of the lot, kills the troll.

And all of the goats get lots and lots to eat, allowing them to get nice and fat.

No, not troll meat! This is a very nice story about cute goats, not a story about consuming the flesh of monsters before they can eat you. Also, by all reports, troll flesh tastes just awful, plus, it has a tendency to turn into solid stone while in the digestive system, which is uncomfortable for everyone, not just goats. No, no. The goats ate very nice grass.

The tale reads very well out loud if you have a proper grownup willing to do different voices for all of the goats and the troll, and a proper grownup willing to make the proper clip clop noises as the goats go over the bridge. (Yes, that’s crucial. Those noises are written into the tale!) If you don’t have a proper grownup—well, it’s still a pretty good story, really. It helps, too, that absolutely everyone, goats and the troll, has the same, immediately sympathetic motivation: they’re hungry. It’s something all three- and four-year-olds immediately understand.

I suspect this is why the story has become so popular as a picture book. After four pages of results, I stopped looking, but can confirm that Amazon currently offers multiple versions from multiple authors and illustrators. True, a few are cartoons, and a few are from the viewpoint of the very hungry troll, but the rest appear to tell retell the story in a straightforward manner—letting creativity go wild with the illustrations.

My own sympathy tends to lie with the many recent authors who have chosen to tell us the troll’s point of view. After all, even in the original tale, in some ways the troll is the most ethical character—in that he isn’t offering up his fellow trolls as fatter, tenderer foods for goats. And in many ways the most sympathetic one: not only does he die at the end of the story, making him the true victim here, but he never gets to eat anything.

It’s a genuine tragedy. I mean, yes, troll, but… let’s all try to have some kind thoughts here. HUNGRY TROLL JUST WANTING SOME GOAT MEAT. We’ve all been there.

Not to mention that we can all learn a clear and obvious lesson from the troll: be satisfied with what you have, rather than believe in promises that something better will be along soon. Especially if these promises are coming from terrified little goats. Though to be fair, the goats also offer a clear and obvious lesson: when threatened by an obvious troll who wants to eat you, point the troll in another direction.

To be fair, that may not always work.

Fortunately, the goats do offer us another moral lesson—that eating a lot and getting fat is the best way to celebrate conquering a troll—something I feel we can all agree with.

Similar tales were collected in Germany by Karl Haupt in his 1863 Sagenbuch der Lausitz (The Lausitz Book of Legends) and by Adalbert Kuhn in his 1859 Sagen Gebräuche und Märchen aus Westfalen und einigen andern, besonders den angrezenden Gegenden Norddeutschlands (Legends, Customs and Wonder Tales from Westphalia and other areas, especially North German lands). These tales tended to use the ever convenient wolves instead of trolls, but otherwise followed the same idea: after hearing that a potentially larger meal might be on its way, the wolf waits—only to get nothing in the end. The Haupt tale offers a slightly disturbing twist: two of the goats have more than one belly.

Buy the Book

Finding Baba Yaga: A Short Novel in Verse

In the Kuhn tale, the twist is that the three goats are a family—a weak little kid goat, full of fear, a mother goat, also full of fear, and father goat, full of the ability to claim that he’s carrying pistols even though—spoiler—APPARENTLY NOT. That said, when the father goat bends his horns towards his leg, the wolf not unnaturally assumes that the intent is to pull out the pistols—and flees.

This adds another twist to the “don’t assume something better will come along” moral of all these tales: a bit of “make sure the goat who claims to be carrying pistols is, indeed, actually carrying pistols before you run off hungry.” And, although this tale does seem to be emphasizing traditional gender roles, what with the mother full of fear and the father driving the wolf away, I kinda have to wonder. After all, the weak little kid goat arrives in the dangerous forest well before his parents do—so well before, the wolf can’t even see the goat’s parents. So. Forward thinking parent goats trying to encourage their kid to have an independent, adventurous life of exploring dangerous forests and occasionally chatting with wolves, or, forward thinking parent goats sending their kid ahead so that something will get devoured before they do. You decide. We can at least agree that these are not overly protective parents.

It’s not a completely unnatural question, given the emphasis in these tales that it’s perfectly ok for the trolls and wolves to eat someone—as long as they are eating someone else.

Despite its lack of such tricks, or perhaps because of that uncomfortable idea of parent goats seemingly more than willing to just offer up their little kid goats as wolf bait, or the comparable obscurity of those particular German collections, the Asbjørnsen and Moe version, as translated by Sir George Webbe Dasent and later retold by many others, became the best known English version of the tale, chosen by Andrew Lang for his 1892 The Green Fairy Book, appearing in several other collections, and warning generations of children to be very very careful when walking over a bridge. No matter what food might be waiting on the other side.

Mari Ness lives in central Florida.

I don’t know if a fairytale can be your jam, but this one is my jam.

My mom did all the voices and the sound effects when she told us to us, and to this day I will bellow out WHO’S THAT CLIP-CLAPPING OVER MY BRIDGE? in my growliest voice whenever I’m feeling particularly troll-like. ;)

Lovely essay, Mari! I shall have to find a five-year-old and tell the version my mother told me, with her sound effects, which, as you say, are extremely important and also fun for the teller.

I could go some curried goat, now I think about it. There are not enough places that does curried goat near here.

Isn’t the story an allegory for the greed of the feudal toll bridge and toll road operators? The guys who ran(or served those who ran) corrupt toll games, and often charged far more than ordinary people could afford?

If you pity trolls reading Asbjørnsen and Moe is not really adviseble.

For random22 trolls in norwegian folklore is often considered a posonification of nature and its harsh/ dangerousness and something to overcome. In the norwegian wikipedia site for this fairytale the crossing of the birdge is considered a journey and conflict between culture (the goats going to sommerpasture to fatten up in preperation for winter – a human conection) and nature the troll threatning to eat them – the wild personificated and its dangers).

When I started reading this I was thinking, “this is a Norwegian fairy tale? I did not know that.” but with a troll as the bad guy, I guess it should be pretty obvious.

Random troll tidbit! Heavy, leaden clouds than hang over the tops of the mountains in the fjord is called “trollsk” [sic] weather. “Its when they come out to do magic,” according to my Norwegian friend while we were traveling on a ferry down a fjord. Makes the half constructed bridge we passed under particularly ominous with how covered in clouds it was.

Glad we weren’t eaten. :)

Huh, I didn’t know that the three goats were supposed to be a Mommy, Daddy, and Baby. I always assumed that they were brothers or just three goats of different ages who just hung out together. I wonder if I woefully misread that simplest of fairy tales for decades!?

It’s not a completely unnatural question, given the emphasis in these tales that it’s perfectly ok for the trolls and wolves to eat someone—as long as they are eating someone else.

I always assumed that the billy goats weren’t actually trying to have their siblings eaten in their places, they were trying to trick the troll into not eating any of them because hey, there’s a fatter goat coming ’round any minute now. Goat 3 just happens to be big enough to fight instead of claiming a fourth goat. Either that, or Goats 1 and 2 know that Goat 3 can take on a troll by himself.

@6 – That was in one of the German versions, not the (obviously correct!) Norwegian one.

ETA

@7 — That was my reading, too. Or, I guess, my listening.

My favorite version of this fairy tale was retold and illustrated by Janet Stevens. In her rendition the goats are three brothers. To emphasize his pitiful size the first goat is wearing a diaper. Goat two dresses like a kid of 8 or 10. The biggest billy goat, however, is huge and really scary in a motorcycle jacket and sunglasses. The troll barely puts up a fight! (But to humanize him slightly, the troll has a pet frog on a leash made of rope, who falls into the river with the troll.) The very last picture is of the three brothers on a picnic blanket eating grass on plates with spoons.

My theory was that the goats were working together and taking a calculated risk. The troll might have beaten the third brother if he’d gone first but, after climbing up and down the bridge three times, he was worn out. They just had to trust their conman (congoat?) skills were good enough to get the troll to let them go so a bigger goat would come along.

“The Haupt tale offers a slightly disturbing twist: two of the goats have more than one belly.”

Explain, please and thank you.

@3

Mmmm. Curried goat. Lots of indian and middle eastern places around NoVa, so it’s readily available. You can get fresh goat at the local halal butchers, too.

“when threatened by an obvious troll “

I know a guy who’s online handle is ObviousTroll, which (in a bit of meta-trollery) he never uses for trolling.

Yes!

Like Jeannie @1, my mom also read this to us complete with voices and sound effects. It was shivery-scary good. As an adult, I am stunned by how few people know of this story. It was so formative for me, to the point where I genuinely feel sad others didn’t have the same experience.

I suppose I shouldn’t be surprised to learn this childhood favorite is a Norwegian tale. The delightful 2010 Norwegian mockumentary Trollhunter has a hilarious/horrific scene where the title character uses three goats and a bridge as bait in a wonderful reference to this folktale. I truly don’t want to say more and spoil anything, and hope I haven’t said too much already. (The film, which was available on Netflix at one point, is very, very much worth watching if you haven’t seen it.)

This was always one of my favorite stories, although I never before stopped to consider why it appealed to me. Thanks for the insights!

@11 Well, goats are ruminants, like cows. And, just like cows, they only have one stomach, but that stomach has four chambers in it. So, that could be what the tale was alluding to (cows are often described as having “four stomachs,” even though the chambers are actually all part of the same single stomach).

It could also be a reference to the myth that goats are so voracious that they will eat practically anything, which I remember being a pretty common joke utilized in cartoons and picture books when I was a kid.

@16: Haha, yes. Gregory the Terrible Eater comes to mind. But I don’t know how that or the ruminant stomach would make the story “slightly disturbing,” or apply to only two of the goats.

Gordon Dickson has a story (“Three-Part Problem” maybe) in which the tale of the billy-goats gruff plays an important part.

I enjoy this story with my toddler grandson. He seems to enjoy the voices and the repetition. We do story time to settle him to sleep. I try to incorporate old tales like Three Little Pigs and The Ugly Duckling as well.

Wondering about the stomaches on the goats. I don’t understand the implication. Retired Lit teacher.